We are pleased to present the new issue of INSIGHT – ARTWORKS IN THE SPOTLIGHT #3, Drawings by Fred Sandback. The three featured works from 1974 and 1982 testify to the genuine potential of Fred Sandback’s drawing oeuvre in the field of tension between spatial situation and two-dimensional paper.

Insight #3 – Drawings by Fred Sandback

Outlines create a shape by delimiting a form and setting it apart from the background or its surroundings. Fred Sandback became known for his sculptures stretched into space, first made with rubber cords and fine metal rods, later with acrylic yarn. The lines evoke sculptural volumes, which occupy and incorporate the exhibition space. The place of execution and its given architectural conditions are thus constitutive for his sculptures. For Sandback, the relationship between space and sculpture is:

“like canvas to the painter or stage to the dancer; it’s what I have to build off of.”1

But what role do drawings play in Fred Sandback’s work? How can they be classified? Are they sketches, preliminary drawings, drafts or studies?

1) Fred Sandback in “Lines of Inquiry: Interview by Joan Simon”, Art in America 85, No. 5 (May 1997) pp. 86–93, republished and translated in Fred Sandback, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein et. al., Friedemann Malsch, Christiane Meyer-Stoll (eds.), Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2005, pp. 135–142, p. 137.

“The drawings have always shared speculative and documentary relationships to my three-dimensional pieces in varying ways.”2

Sandback’s drawing vocabulary closely revolves around the typology of his sculptures, specific exhibition spaces of galleries or museums and spatial situations in general. Sandback kept a sketchbook, which he used as a field of experimentation. In addition, there are a few quickly sketched notations that can be assigned to specific sculptures and exhibitions. The majority of his works on paper, however, consist of autonomous drawings that were not made in preparation for sculptures.

Rather, they are like musical scores of possibilities. They allowed Sandback to repeatedly examine and test exhibition situations and work types in ever new combinations and relationships. Through drawing, the artist thought about what was, what is and what could be.

2) Fred Sandback in “Lines of Inquiry: Interview by Joan Simon”, Art in America 85, No. 5 (May 1997) pp. 86–93, republished and translated in Fred Sandback, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein et. al., Friedemann Malsch, Christiane Meyer-Stoll (eds.), Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2005, pp. 135–142, p. 136.

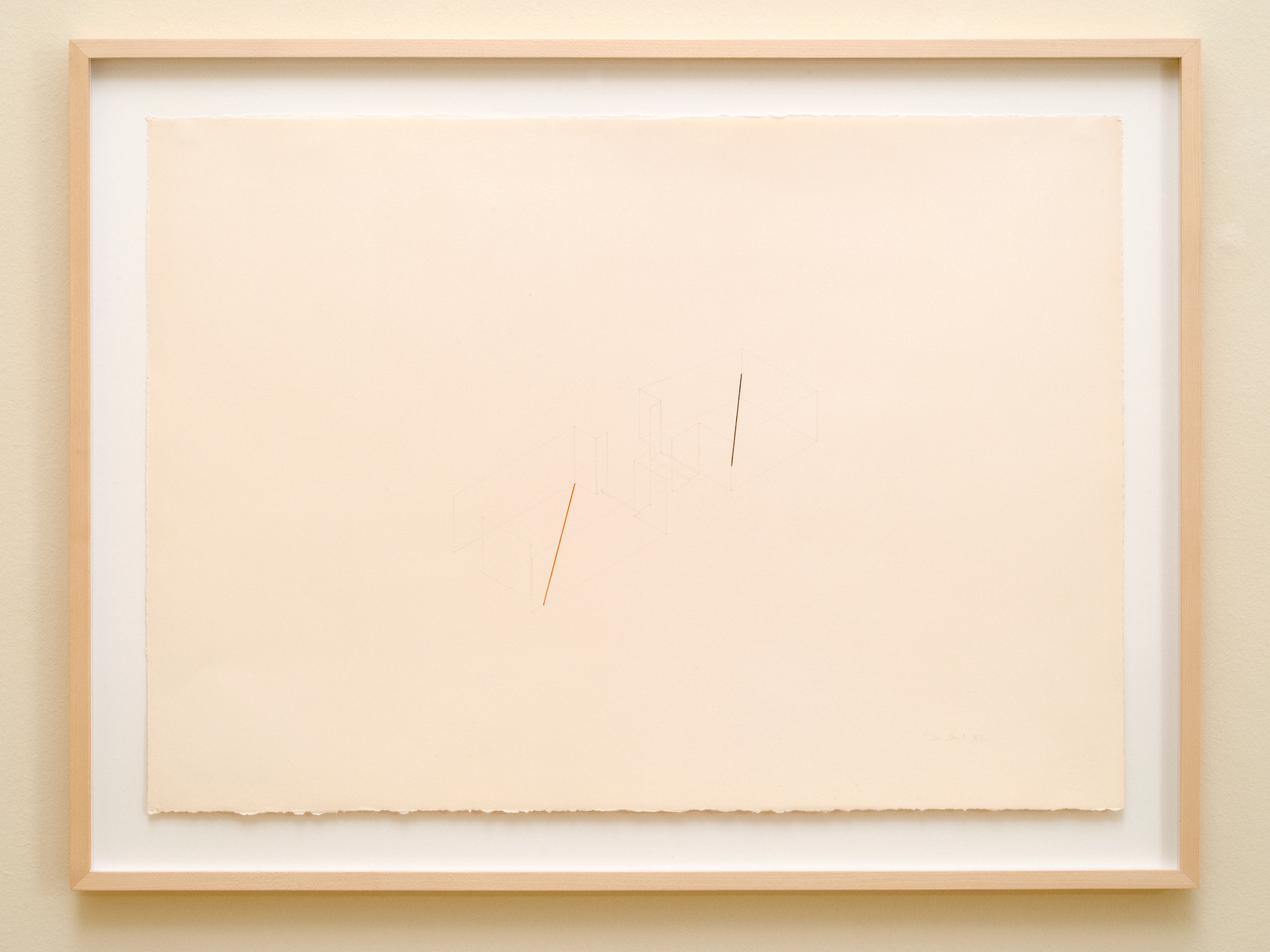

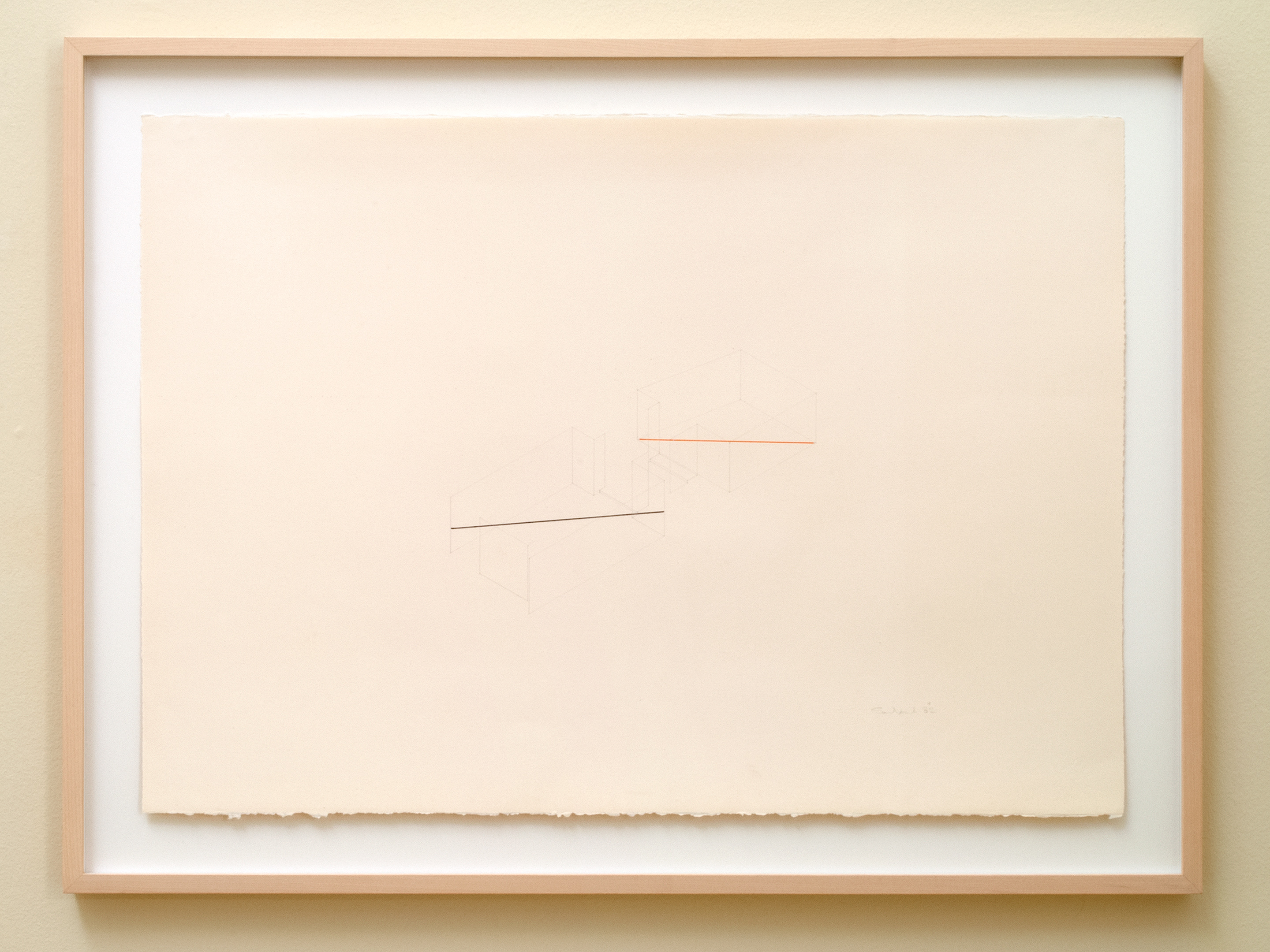

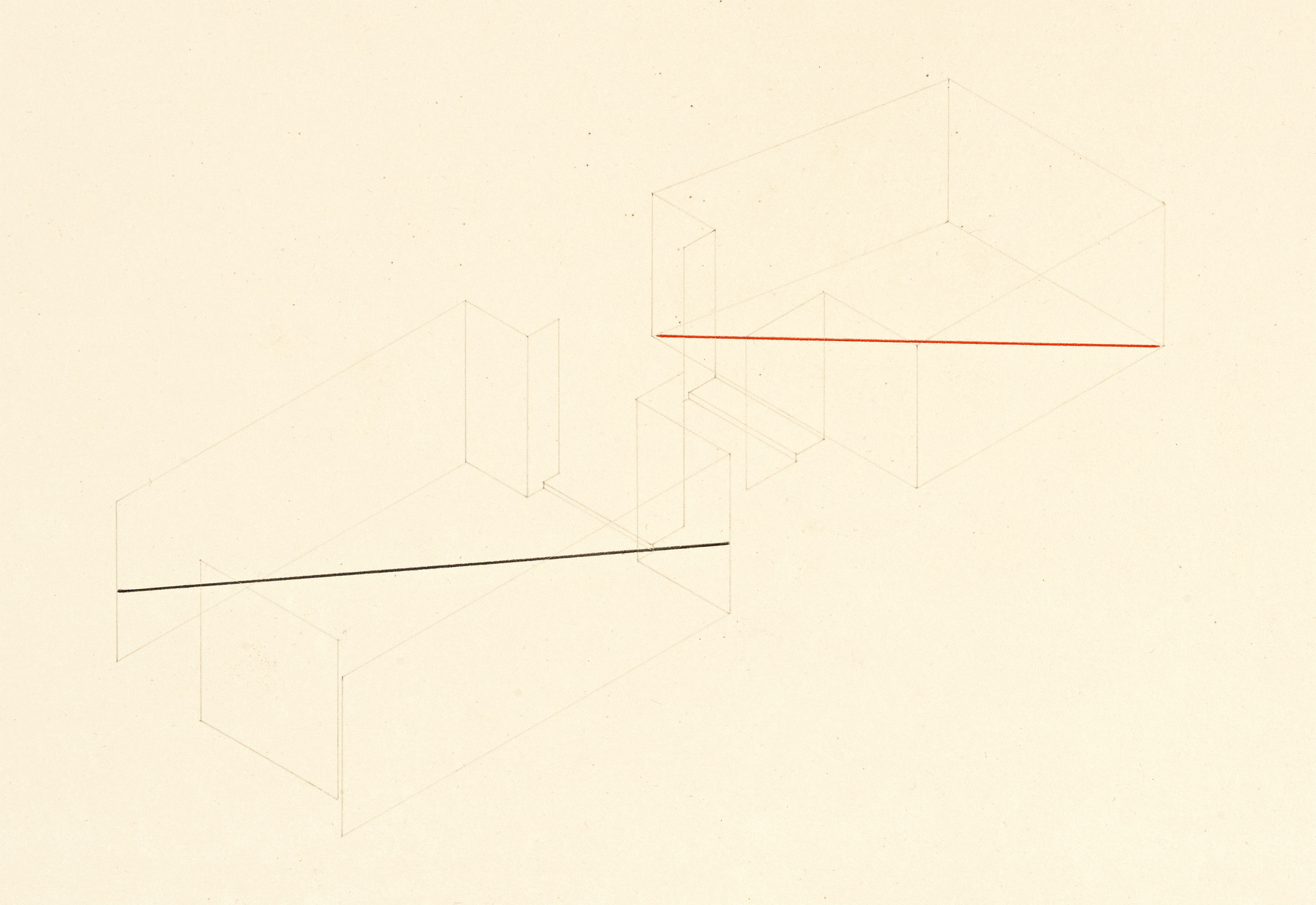

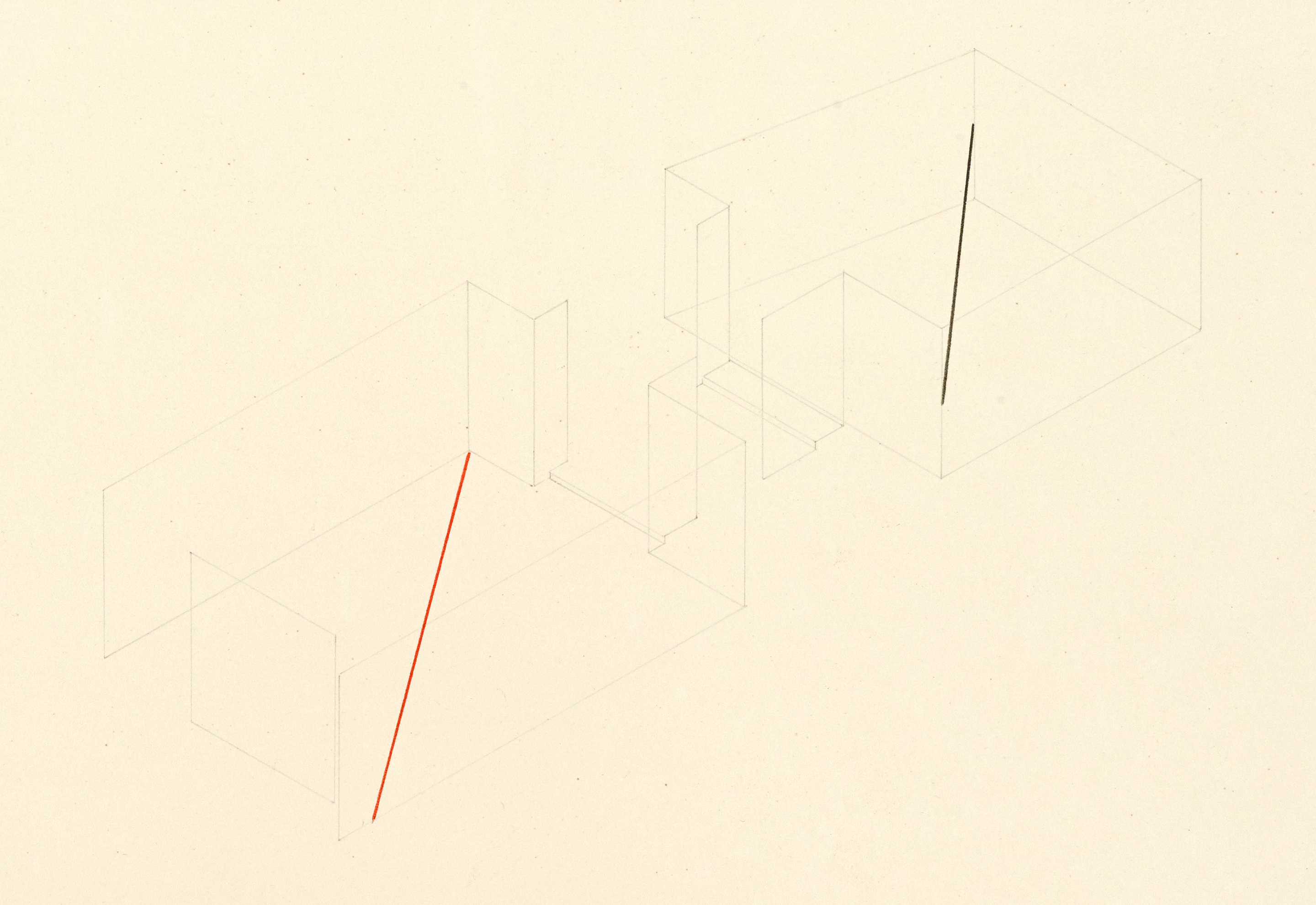

The two Untitled sheets from 1982 exemplify the type of drawings in which Fred Sandback depicts a specific place, in this case Galerie Editions Média in Neuchâtel (CH). Marc Hostettler presented a double exhibition here in 1982 with Fred Sandback and Lawrence Weiner. Under the title One of 16 Sculptures in Two Parts and Two Colors, Sandback developed a two-part sculpture for the two gallery rooms on the ground floor. In the first room, he stretched an orange string along the diagonal of the floor. In the second room with walls painted gray, a piece of black yarn traversed the space in the same direction at a height of about 120 cm.

The title of the sculpture refers to the possibility of positioning the two yarns in 16 different ways. Only one version was shown during the exhibition.

Understanding sculpture as a sequence of different situations, varying the sculptural arrangements and applying them in different spatial situations is fundamental to Sandback’s work. His sculptural vocabulary was never intended to cover the broadest possible range of conceivable solutions, but instead forms a concentrated selection of different work types which he repeatedly applied over the years.

For Sandback, the potential of his sculptures resided in the aspect of time as well as in spatial changes. The two Untitled sheets from 1982 bear impressive witness to this. They were created during the exhibition in Neuchâtel and show alternative positionings of One of 16 Sculptures in Two Parts and Two Colors.

In the two Untitled drawings from 1982, the two-roomed ground floor of the gallery is rendered with fine pencil lines. Sandback inscribed a two-part string sculpture with red and black pastels. The two sheets are a variation of diagonals. The red lines run along the floor, the black ones at around the halfway point of the room height. In direct comparison, the two drawings are visually very different. While the horizontal dominates on one sheet, the vertical is more prominent on the other. Nothing has changed in the spatial situation. But the placement and orientation of the two lines have been mirrored in reverse, and they have exchanged their spatial context.

Fred Sandback chose an isometric view for the representation of space. This means that the space and the depicted bodies are not oriented towards a vanishing point. Parallel lines are not distorted in perspective, but always extend at the same interval. Corner points can tilt forwards, or into the spatial depth.

The clear distinction between background and foreground is thereby eliminated3, as the depicted architectural situations and sculptures vacillate between three-dimensional space and two-dimensional surface.

The point of view and isometric depiction cause the two sculptural situations to look completely different in the two Untitled drawings from 1982, though they would appear very similar in the actual physical space. Spatial experience is thus only of limited help when reading Sandback’s drawings.

This ambiguity accounts for the discrete character of Sandback’s drawings, as they allow us to experience sculpture in a way that is not possible in real space.

3) Vazquez, Edward A.: “Der Zug des Raums”, in Fred Sandback. Zeichnungen, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Winterthur et al., Dieter Schwarz (ed.), Richter Verlag, Düsseldorf 2014, pp. 174-182, p. 178.

“[…]some [drawings] speculate about a place that doesn’t exist, others about a place that does exist, and others are mixed up in nostalgia, the memory of a place that has existed. There are exhibition designs that I have never realized.”4

The two Untitled works from 1982 show how strongly Sandback’s isometric drawings emphasize not only the peculiarities of each of the depicted sculptures, but also of the respective location. Differences in level, proportions, deviating angles and through-passages transform architectural spaces into uniquely differentiated places. These can be situated and recognized within the genesis of the works. The drawings enabled Fred Sandback to view the gallery and museum spaces from a different perspective and from a standpoint outside the site of artistic action. Drawing provided a means of engaging with them beyond the duration of an exhibition. “Fred really and truly had the habit of collecting the spaces from his previous intensive working experiences.”5 In this way, he had access to spaces that remained closed to him outside of the realm of drawing.

The two drawings from 1982 belong to those made from about 1970 onwards in which work and space are intertwined. Over the course of his artistic life, Fred Sandback developed further drawings starting around 1980 in which he exclusively engaged with space. In these pastel crayon drawings, he was interested in the different aspects of spaces, such as the volume of a room, wall boundaries or light coming in through doors and windows.

In contrast, going back to the years from around 1973, he produced drawings with sculptures freely positioned on the paper as lines without reference to space.

4) Fred Sandback in “Sandback: où est la sculpture?”, interview in Sans Titre: Bulletin d’Art Contemporain, Lille, No. 16, January–March 1992, pp. 1–2, republished and translated in: Fred Sandback, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein et. al., Friedemann Malsch, Christiane Meyer-Stoll (eds.), Hatje Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 2005, pp. 127–130, p. 129.

5) Verna, Gianfranco, “Fred Sandback”, in Fred Sandback. Zeichnungen, exh. cat. Kunstmuseum Winterthur et al., Dieter Schwarz (ed.), Richter Verlag, Düsseldorf 2014, pp. 75–79, p. 77.

The drawing Untitled from 1974 shows such a sculptural situation without spatial fixation. Two lines in blue and black cross the approximate center of the sheet in a slightly diagonal direction from bottom left to top right. The two lines, the black one shorter than the blue one, are parallel. Neither the lengths nor any possible points of intersection or alignment seem to be executed according to any sort of grid laid out precisely in relation to the sheet. Rather, they are freely placed on the page. The determinedly applied pastel pencil vividly translates the fibrous texture of the acrylic yarn that Fred Sandback most typically used for his sculptures. The pastel strokes have a tactile quality.

While the sculptures in drawings such as the Untitled works from 1982 are inscribed with relatively delicacy as part of a spatial situation and at a great distance from the viewer’s standpoint, the autonomous lines in Untitled from 1974 are strong and self-consciously put on paper. They have risen from the depths of the sheet to its surface and converge on the viewer’s space. In the process of this convergence, the lines shift from their representational function and emancipate themselves from the (purportedly) represented sculpture.

“He is concerned with the ambivalence of the line, its ambiguity. A line can portray something or merely be the line itself, representing or presenting, generating illusions or doing away with them.”6

Thus freed, the lines of Untitled from 1974 are open in their spatial and ontological conception. In consideration of Sandback’s vocabulary, it is legitimate to persist in interpreting them as sculptures. The sheet of paper then functions as a spatial component, either as a wall on which the yarn sculptures directly rest,7 or as a spatial volume within which the lines can be understood as diagonal connections between wall and floor.

At the same time, however, it is also possible to detach the drawing from any spatial location. It is then the characteristics of the strokes, the application of the pigments with the pastel pencil, the proportions and in this context the different coloring, as well as the placement within the sheet, which constitute the drawing. In the process, a particular simultaneity of calm and tension becomes perceptible.

The small selection discussed here exemplifies how Sandback’s drawings offered him possibilities that go beyond working with actual sculptures in real space. The drawings are not in the service of the sculptures, nor are they merely aids in the conception of new three-dimensional works. They are works in their own right with a decidedly individual aesthetic, which enable the viewer to have a completely different experience from seeing the works in the exhibition context. (Text: Laura Mahlstein; Translation: Julia Thorson)

Insight #3: download here as a PDF

6) Verna, Gianfranco, “Foreword”, Fred Sandback. Drawings 1968–2000, exh. cat. Annemarie Verna Gallery, published by Annemarie Verna Gallery, Zurich 2005, p. 30.

7) Referred to as wall constructions, such sculptures in the form of yarn drawings on the wall were presumably first created in the mid-1980s.

Images: Copyright © 2022, Fred Sandback Archive

The drawings were part of our exhibition

New Rooms – Fred Sandback und Sol LeWitt.

We look forward to showing you the artworks in the gallery.